Can’t Get Enough Havana

![]() We’re invited to see Black African rumba dancers in Hamel Alley painted by artist Salvador Gonzalez

We’re invited to see Black African rumba dancers in Hamel Alley painted by artist Salvador Gonzalez

The Havana terminal seemed familiar, like other Latin airports I’ve wandered through but larger. Humid, crowded, families in free fall, Caribbean. More planes than ever are gliding in, delivering the curious.

We are meeting our trip organizers Pepe and Bette, but where? Claiming the bags seems wise. She’s sent us a JPG of a redhead arriving on a flight from Miami who we are supposed to collect somehow too. Chaos and kin. Amazingly, red head she finds us.

Pepe responds to musicians’ vobe at a rest stop on our way to the beach.

Then, yes. That’s Pepe. We are rounded up, our bags stuffed into taxi vans. There is young Fidel (buried a week earlier) on a billboard with Raúl. We pull up to the garden door of our small hotel in the upscale Vedado neighborhood. The staff, men and women, grinning welcome, grab our bags. It’s frustrating that I can’t toss out any of the Spanish I once knew, pitiful even then.

Casa Nostra, our private hotel, is decked out with fantasy and fuss.

It’s hot. Casa Nostra, our private hostel, is a Tennessee Williams stage set. Wildly glamorous with porcelain swans, long-stemmed fabric tulips, gauzy curtains and satin drapes, columns everywhere, Ionic in the living room, Corinthian in the bathrooms. A small saucer of chopped fresh tropical fruits — pineapple, guava. and papaya — for each of us. Cool and refreshing.

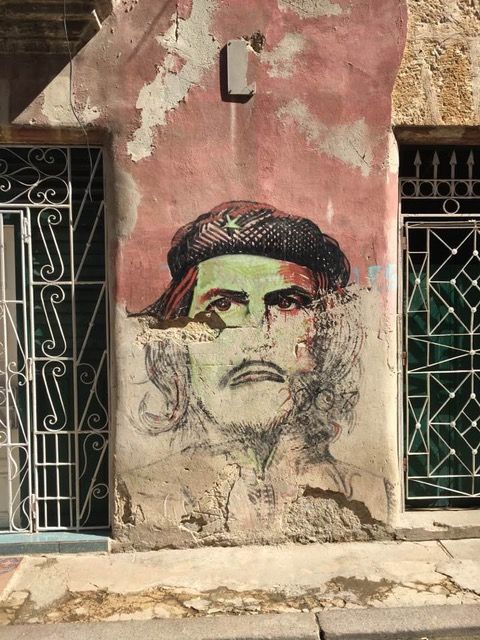

A friend photographed this wall the week before we arrived. Credit: GorillaSuitProd

There is no light or electrical outlet in two-thirds of my room though there is air-conditioning and a small fridge. Workmen with a ladder add two bulbs to the lone 15 watt nub in the fixture near the door so I can read in one of the two fancy overstuffed chairs. At night I use my small flashlight to find the bed.

Lorenzo wheels us around in his family’s exquisitely preserved ’59 Impala. So sweet, speaks English too.

We are eight pilgrims signed on for this adventure orchestrated by Bette and Pepe, Cuban afficienadoes. Her documentary, A Cuban Legend, the story of artist Salvador González, won raves for how it captured Havana street life. Everyone wants to take a walk after unpacking. And then a nap, before we pile into the two gloriously preserved vintage cars Bette has rented for the ride to dinner. Cuba is cash only. The Convertible Peso — Cuban CUC — costs $1.12. There are no ATMs. Credit cards are not honored in Cuba. American Express will be shocked by my silence, possibly assuming I’ve been kidnapped.

Bette and Pepe took Chef Carlos Cristóbol to a wholesale market to shop for Citymeals Que Rico! last June.

Our troupe is far from the biggest deal to dine at San Cristóbal Paladar, a 20th-century mansion on a narrow cobbled street. That would be Michelle and Barack and, certainly, Mick. But Citymeals on Wheels flew chef Carlos Cristóbal Márquez Valdés to New York to cook at Que Rico!, our Latino fund-raiser at Rockefeller Center last June, and he’s been waiting since then to feed me. The vast, two-story space is amazing, both grand and funky.

Pepe introduces us to the waiter who served The Obamas. His life will never be the same.

With the revolution sweeping in and confiscating everything in 1959, the wealthy businessman who built it gave it to a servant, Carlos’ grandmother. That’s why the powder room includes a giant tub and shower. The house is full of their books, precious tabletop, religious heirlooms, and antiques. Carlos is an incurable collector, too. He and his mother have added to the museum. When people have something old to sell, they bring it here.

I think the after-dinner cigars were meant just for the men at Cristóbol but one of us demanded equality.

Our table is set with lace and damask, silver and crystal. Behind it, an alter; on the wall, dozens of clocks. After the mojito of welcome, appetizer platters are set down with an assembly of small dishes: garlic octopus, deep fried fish, various cheeses, malanga fritters, Spanish tortilla, caramelized eggplant, smoked salmon, and ceviche. The friendly English-speaking waiter who pours each of us rum offers suggestions for what label we should buy to take home.

There are always vintage costume jewelry brooches for the women. I think Peter took one too.

I consider the oxtails. But everyone is ordering langoustine, so I do too, finding it surprisingly fresh and not overcooked. Pudding with fruit and almonds simply arrives. And with the coffee, cigars for everyone, and a collection of costume jewelry pins for the women to choose from. Maybe it isn’t the best meal we’ll be having in these next eight days, but I’d definitely send you to Cristóbal.

Cecilia from Miami caught this woman taking the sun in her doorway.

Walking is the way to see old Havana. The cobblestone streets are narrow, the sidewalks broken, tilted and even narrower. Storefronts are alternately lavishly restored or falling apart. My camp mates, I discover, are big-time shoppers. Everyone seems to be buying fancy fans. There is a silent woman in the fancy fan shop to paint your name on any purchase. I buy a turquoise beauty.

My pals were all buying fans. What could I do? This woman will paint your name on the handle.

No one has asked me to bring any cigars home. That’s how bad my romantic situation is.

No one has asked me to bring any cigars home. That’s how bad my romantic situation is.

“People to people,” we circled as our mission on the $25 visa we bought at Newark airport. We are definitely meeting the sales clerks. Our committed consumers wander into a cigar store to check on prices. I buy a few samples in the fancy chocolate shop. I weigh the purchase of a tote bag honoring Che Guevara from one of the many lookalike souvenir shops. I finally surrender to a canvas bag with an image of Frida Kahlo and Che on a red tee for my grandson Zac.

The supermarket at the new mall was well stocked with local rums and booze from everywere.

I am eager to see how Cubans live, the neighborhood markets, farmers markets, supermarkets, bakeries. Pepe takes a few of us to a market in a new mall where ceiling tiles are still being pounded into place. The liquor department is well stocked and there are Swiss chocolate bars. The fruit cocktail is from Vietnam, the cleaning products mostly Russian. I buy some local cookies. There are many empty cold boxes, and only two chickens and hot dogs in the butcher department.

The neighborhood bodega where I bought our yogurt was sparsely stocked too.

Later that afternoon in a spottily stocked bodega, I find a tall canister of plain yogurt and Belle buys slices of orange-colored cheese. I have to suppose this is the poverty that our embargo creates. I can’t make up for it by giving $5 CUC to the maid who hand washes my laundry, or leaving the tasteless cookies for the kitchen crew to finish. Most of the produce I see in markets is bruised and small. Pepe buys green oranges so I can have o.j. for breakfast. The bread is normally soft and white, but perhaps that is what the Cubans prefer.

I think these are limes at $5 CUCS a pound but they look just like the green oranges Pepe bought.

The dull green of canned asparagus that evening sets off eyeball rolls.. Bette apologizes for the listless dinner at Monseigneur, a government restaurant chosen so we can walk after to where special buses wait to deliver us to the Karl Marx Theater for opening night in the 38th Annual Havana Film Festival. Pepe is excited to run into his sister from Puerto Rico. The stars supposedly gathering to party at the Hotel Nacional afterward may have sneaked away to congregate elsewhere. Why is no one surprised?

Bette hadn’t seen this shop offering a view of the skies before so she stopped in to check it out.

Everything was delicious at our Habana 61 lunch, starting with this delicate crudo.

Bette has arranged for an artist to lead us on a tour of Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, emphasizing the Cuban art. Afterward, we gather around tables pushed together at the smart, green and black Habana 61 for lunch. There are $2 CUC daiquiris, fish croquettes and malanga fritters with honey for dipping, and fabulous octopus in olive vinegar with peppers. At the far end of the table, four of us share a portion of ropa vieja with beans and rice. It’s the best food we’ve had so far. Calle Habana #61. (537) 8016433

We shared Habana 61’s fish croquettes and these crispy malanga fritters. Repeated elsewhere.

Habana 61’s octopus carpaccio looks like some we see in New York but at a modest Cuban price.

There’s an outdoor café next to the tall chimney at El Cocinero, a souvenir of its industrial past, but our table in the dark, dining room proper with its upscale crowd is just one flight up. By the time our attractive young captain confirms that a spot for us has cleared on the terrace, we are already drinking cocktails and voting not to move. I start with lumpen Chinese dumplings — a welcome variation from malanga fritters — followed by excellent duck confit. I taste my neighbor’s lamb curry. It’s good too.

El Cocinero in a former factory is dark and sophisticated, attempting a global cuisine. Like my duck confit.

That’s the night that one of our crew gets sick. Shall we call it Fidel’s revenge? I wonder if his delicious raw lamb appetizer is to blame. No one suggested we should bring Imodium and Cipro to Cuba, just in case. I went armed to India, but never thought I might need my medicine chest in Havana. Happily, I never did. Calle 26e/between Calle 11 and13, Vedado. (537) 8322355.

Porto Habana has breeze from the open window, art deco décor and a fabulous view from the 11th floor.

We had cured ham and tomato Bruschetta to start at Porto Habana. Then Belle wisely ordered fish fillet.

Porto Habana seems hard to find, but there is someone waiting inside the building to press the button for the apartment on the 11th floor that has been turned into a paladar with exotic lamps and vases and a fabulous view. A table for ten is reserved every night at 6:30 for a group of international medical students. A breeze flows in from the open windows.

Did we pay $1 CUC to take Porto Habana’s magnet fork-rest home or did we just steal them?

We start with the essential malanga fritters for all, and assorted bruschetta. My pork chunks are too tough to chew, but Belle’s fish fillet is excellent. Apparently, it’s okay to take home the pink ceramic magnet that serves as a fork rest. Calle E no.158B between Calzada and 9na, 11th floor. Plaza de la Revolución. (537) 8331425

I sipped a seven-year-old rum cocktail, then tackled El Litoral’s excellent buffet with plate-filling verve.

There’s an antipasto option but I opted for the big plate – and was amazed at how big it was.

Even as a child, I was a fool for buffets. I arrived in New York City just in time for the last of the Scandinavian smorgasbords. So I’m in heaven at El Litoral as soon as I spy the buffet option, especially after a few sips of the excellent house drink, Canchanchara — 7-year-old rum with honey, lime, and a squiggle of lime rind.

You can choose a small plate for the buffet and then order an entrée from the menu, or fill a large plate. The large plate is actually very large, and I am an expert at using every half-inch of space. A friend watching me is stunned to see how much I have piled on. Rice salad, potatoes painted with tuna, pasta salad, quiche, cheeses, charcuterie, octopus salad, salade Russe, olives, pickles and peppers. I don’t even long for a rerun because I am quite full. And then there are the ice cream desserts. Mine, strawberry with vanilla custard and tropical fruit, is luscious. Malecón. (537) 8302201

El Litoral had several ice cream deserts too. Mine is strawberry with custard and tropical fruit.

A trio of filmmakers, including Estrella Bravo and Barbara Kopple, join us on the terrace of Paladar Vistamar in Miramar, where the surf slaps up against the wall but never spills a drop. We are in time to watch the sunset. Before the revolution, each house on this stretch had its own pool on the ocean. The paladar is not new, and the staff is experienced. I’m trying to decide between a daiquiri and the house’s famous sangria. Chef Pedro Pablo Rodríguez (also at Habana 61) sends ceviche as a gift and comes by to say hello.

I decided to have the Caesar with shrimp at Palador Miramar in what was once a seaside mansion.

I’m still feeling the effects of too much enthusiasm at La Casa del Gelato only two hours earlier. My Caesar comes with shrimp alongside to add or not. Peter has announced that it’s his birthday, so we’re not surprised when something chocolate arrives with a candle on it for him to blow out. Avenida 1ra No.2206, between 22 and 24, Miramar. (537) 203 8328.

There are carts selling ice cream and corn on the cob and here, churros with syrup.

Friends ask how was the food in Cuba? Surprisingly good. Use these recommendations if you go. Maybe the many pressed Cuban sandwiches I had in outdoor cafes weren’t perfect — too chewy ham, too soft bread — but those $2 CUC cocktails will leave you mellowed. Havana is not yet besieged by tourists as Venice is.

But I was disturbed, of course, on returning home to find a NY Times report that tourists are taking the food out of the mouths of Cubans. The dispatch reported that official price ceilings had done little to get good, affordable produce to Cubans. It described government markets with many starches and bruised fruits like some of those I’d seen. (Click here to read the Times story)

An eyeglass seller and a bakery share space.

It seems the co-op markets where rarities like grapes, celery and ginger are piled high, have become the playground of the private restaurants that serve people like us. Many Cubans cannot afford the prices restaurants pay. Once there were only a few secret paladars. Now there are 1,700 private restaurants across the country. Cubans learned to do without when the Soviet Union collapsed. Then the population was 7 million. Now it is 11 million.

It’s afternoon, so there is only this lone shopper in the almost deserted market.

Laura Fernandez, a manager at El Cocinero, a former peanut-oil factory converted into a high-priced restaurant is quoted arguing that it’s not only the fault of the private entrepreneurs. “There is generally a lot of chaos and disorder in the market,” she says. Misguided government agricultural policy has affected farming as well.

Our buffet lunch at the home of Artist Salvador González in his astonishing Hamel alley.

There may be some likely visitors who might not want to be part of this imbalance. We dined out in innocence, but reading this dispatch can make you feel uncomfortable. Obama meant his Cuban reforms to stir a demand for more freedom. So far, our unpredictable twitter president has not put his stamp on our Cuban policy. Who knows? He may demand a deal where the Cubans get fed too. Or American tourism could be turned off. And hunger will only grow.

In her role as restaurant critic of New York Magazine (1968 to January 2002) Detroit-born Gael Greene helped change the way New Yorkers (and many Americans) think about food. A scholarly anthropologist could trace the evolution of New York restaurants on a timeline that would reflect her passions and taste over 30 years from Le Pavillon to nouvelle cuisine to couturier pizzas, pastas and hot fudge sundaes, to more healthful eating. But not to foams and herb sorbet; she loathes them.

As co-founder with James Beard and a continuing force behind Citymeals-on-Wheels as board chair, Ms. Greene has made a significant impact on the city of New York. For her work with Citymeals, Greene has received numerous awards and was honored as the Humanitarian of the Year (l992) by the James Beard Foundation. She is the winner of the International Association of Cooking Professionals magazine writing award, 2000, and a Silver Spoon from Food Arts magazine.

Ms. Greene's memoir, "Insatiable, Tales from a Life of Delicious Excess"(www.insatiable-critic.com/Insatiable_Book.aspx )was published April 2006. Earlier non-fiction books include "Delicious Sex, A Gourmet Guide for Women and the Men Who Want to Love Them Better" and "BITE: A New York Restaurant Strategy." Her two novels, "Blue skies, No Candy" and "Doctor Love" were New York Times best sellers.

Visit her website at: www.insatiable-critic.com