The Rising Son of Satsuki at Suzuki

The $250 omakase at Satsuki in the new Suzuki had pretty preludes including this sashimi dish.

You might say we have come too soon for the $250-per-person seduction, but I disagree. Satsuki’s pale oak omakase counter and the adjacent Three Pillars bar at Suzuki have just opened in a mysterious cellar on West 47th Street. Lauren and I have the master himself focused only on us at the near-deserted sushi bar.

I like to start with uni, middle with uni and end with uni which almost never happens.

It’s my first night out braving the ice and snow and slush of the big blizzard, and many gutters and sidewalks are treacherous, but I’m not worried. They’re Japanese, I tell myself. They’re brand new and focused, so they will have cleared the pavement and street in front of their door.

The master Toshio Suzuki previews the collection of fish that will become sushi tonight.

But no. I’m shocked to see Lauren, still bundled up, and an overcoatless young Japanese man struggling through the grungy plowed pileup to grab my hand and guide me over the ice to the unkempt sidewalk and to the door at 114 West 47th Street. I’m so shaken and annoyed at the very concept of an ambitious revival by the powers of Sushi Zen letting this icy barrier stand that I don’t see the name etched on the glass or even the flowers.

This is opening night of Satsuki, the very beige sushi bar at the new Suzuki, and we are only four eating.

I only notice the wait for the inauspicious elevator taking us to a below-pavement labyrinth, not quite finished, decked out in eggplant and black. A greeting stand. A place to leave our layers or wraps. We bypass a busy little cocktail bar and are led into the 10-seat sushi sanctuary. At the far end a chef devotes himself to a couple, the only other customers. We are delivered to the immediate seats. “Here you have Toshio Suzuki only for you,” we are told.

It is all very beige, the paneled wall behind, the rough oak counter with its unfinished bark edge, very sedate, almost non-committal. A large ceramic bowl in the corner behind the chef and some modest flowers are the only attempt at fuss.

The intimacy of the sushi bar is intensified when it is just the two of you and the master himself.

I recall this handsome old man with his long white hair pulled into a ponytail from my one long-ago visit to Sushi Zen. I assume the lights are meant to illuminate his face. Alas, they light the back of his head and cast a shadow on his expression.

A second wooden box holds the tuna offerings and sea urchin, for your inspection.

I note his gravity and grace and watch his hands in the spotlight as he shows us the evening’s catch in a pale wooden box, caressing each filet as he names it. The horse mackerel, the golden eye snapper, the needlefish, the octopus. Lauren orders a carafe of sake for us to share as Suzuki wrestles a second show-and-tell box to the work counter, reciting for us the source and rank of the various cuts of tuna and sea urchin.

I suppose we could have splurged on a more rarified sake but dinner already costs $335 each.

Behind us, a hand delivers the rolled wet cloth in a little carrier. And then a small drink in a pretty embossed liqueur glass: Yuzu, gin and “What did he say?” I’ve read that it mixes single malt Scotch, tomato juice, Yakima salt, raspberry, daikon and yuzu, created by Alex Ott, the German bartender whose drinks supposedly provide “ancient energy” and act as a “gym substitute.” Is that possible? It would be smart if it were mostly gin. I need a little extra mellowing.

This little wooden carrier reminds me of the doll house I always wanted as a kid but never got.

The waiter brings a pretty like wicker carrier — dollhouse furniture holding a duo of small, decorative bowls. You have to pull them out to taste. In one, there are slivers of scallop with scallion and Japanese mushroom. In the other, black sesame gelatin topped with a Japanese gluten cake. The gelatin is elusive, chopsticks breaking it up en route to your mouth. Out of the corner of my eye I see Lauren giving up. I’m too stubborn, shoveling away. I consider abandoning the chopsticks and licking the bowl. But I sense that might be too carnal for the old guy.

Here’s my co-conspirator Lauren Bloomberg’s shot of the sashimi with three dipping bowls.

Here’s my co-conspirator Lauren Bloomberg’s shot of the sashimi with three dipping bowls.

Daddy delivers corsages of sashimi, one for each of us: striped snapper, jack mackerel and “fatty tuna from Spain,” he annotates, as the waiter sets up three bowls for dipping. I never use soy with sushi or sashimi, but I like the ponzu mix. Another prelude to the sushi parade.

I like Lauren’s iPhone overhead of the ethereal octopus and the monkfish liver, a prelude to sushi.

The next fancy prelude to sushi has the remarkably ethereal octopus in a royal blue glass bowl, and slices of monkfish liver inside a small, brilliantly-colored covered china ball. I’m supposed to dab up the sesame seeds in a dish alongside – with the liver, I think, but maybe it goes with the unworldly octopus. It’s one of those moments. I decide, when you’ve committed to paying $250 dollars plus tip and you should just enjoy it.

It’s hairy crab season, but this crab is not hairy, the chef promises us.

Hairy crab from Sapporo winged with a green leaf and arranged under radish like a brooch is next. “Of course, not hairy,” the chef assures us. “Hairless.” He mentions tomato water and dashi roe, but the tomato must have fainted because it’s definitely very faint. “Of course, each season brings a different crab,” Suzuki footnotes.

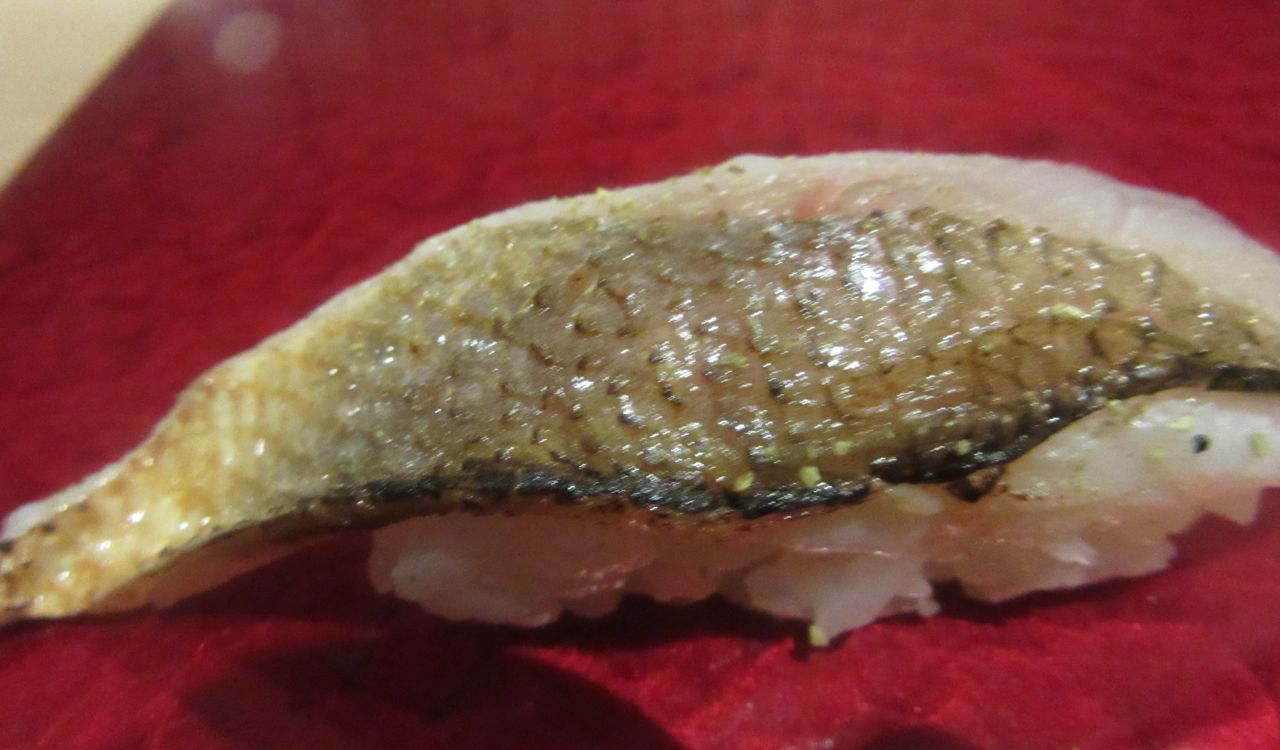

He drops a bundle of preserved ginger for each of us and places a sushi for each on the ledge between his station and our perch. The ribbon of squid is incised with a ridge, touched with sesame salt. I put it into my mouth whole, finding it unusually tender and delicate, provoking a belated ohhhhh. Next comes “pickled fish, like a herring,” as he describes it, with a sheet of pressed kelp on top. Another sensuous gasp.

Golden eye snapper with its crackling skin is one of the triumphs of the sushi parade.

Golden eye snapper. Needle fish pressed between two sheets of kelp “to take off the water.” Otoro, that fatty tuna from Spain. A very strong, brown, not terribly pleasant tuna, marinated with salt and yuzu and other mysterious things the master won’t identify.

Toshio says this is a “herring-like” fish with a cloak of pressed kelp. Full of pow.

“Do you like the rice??” he asks. It’s a vinegared mix of two varieties, he tells us. “Do you like the size of the rice? Do you want it to be smaller?” I find it beguiling that he would ask. He seems pleased as Lauren invokes the names of fish in Japanese, and is delighted to discover we have each spent time in Japan. We speak of eating early morning sushi in Tsukji, the fish market.

He must have washed his hands 20 times. Now he shells the Kuruma shrimp which are really prawns, he notes.

Raw prawn sushi.

Raw prawn sushi.

There is a pause while he peels kuruma shrimp for us. “It is really a prawn,” he corrects, delivering them raw on rice. A sliver of Whiting “from Chibi prefecture” is seared on one side, a currently fashionable look on designer runways. Am I high from just the small glass of sake?

A bulbous huddle of eel from Hokkaido is delivered on a rough cut ceramic tile.

But it could be the coming of the uni, “from Hokkaido,” plump and nuzzling together on a small cushion of rice. That’s a high, too. I’ll spare you the uni swoon…but yes, there are two. Soon I am staring at a significant twist of eel from Tsushima Island, crouched on a ceramic square.

The chef seems very proud of the medium fatty tuna from Spain. Sushiko is known for his product demands.

“This looks like tomago,” he says, delivering what is definitely not the usual egg cake. “It’s made of shrimp, whitefish, tofu and egg,” he confides. Exciting, no? Alas, it’s totally tasteless. Lauren and I stare at each other. I roll my eyes.

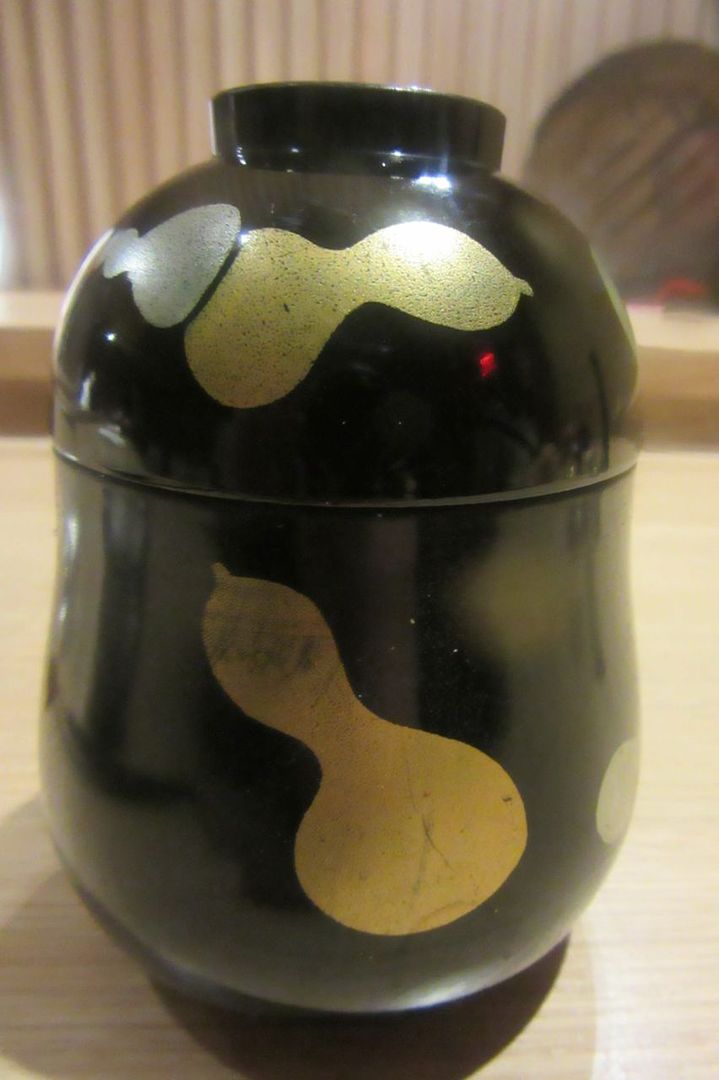

Red miso soup is a wonderful palate cleanser as sushi gives way to the finale.

Red miso soup with wakame seaweed may be poured from the handsome lacquered pot into its cover, a classic kaiseki treasure. You might think you don’t really need soup, but you do. Sip and savor the broth. It’s another complex drama to signal the end of sushi.

Tuna from Spain goes into the fat and delicious handroll which is more remarkable for the crackle of its nori.

He fashions a hand roll, filled with more of the lush fatty tuna plus radish, scallion and bonito flakes. I’m trying to remember the last time I had nori quite this fresh and crisp, a seaweed trick, breaking off at the touch of a tooth. He looks at us and raises empty hands as if to say, That’s all, folks.

Chefs stand. That’s the way it is. But two and a half hours is a long time. Suzuki looks tired.

As the counter is tidied up in front of us, I ask about the wood. “It’s oak,” he says. “Americans like oak. The Japanese like cedar.” I notice it’s not in one piece like the rare, imported slab at Masa. I sense Toshio Susuki is unhappy about the oak too. Now, in the pause before dessert, he decides we need to know more about him. He teaches at the International Culinary Center, he tells us. And at Astor Center too. “I showed them a whole eel and how to kill it and skin it. I showed them pickles. I showed the special way to kill fish.”

I’m not supposed to eat grapefruit so I can’t have this citrusy little gelatin cake that goes to Lauren.

A waiter brings a pretty little berry doodad with grapefruit gel to Lauren for dessert, but not for me. I’d said I don’t eat grapefruit, so I get two weird, crunchy sandwiches, mysterious and not at all delicious – one filled with vanilla ice cream, the other with red bean paste.

A duo of unappealing cookies – one stuffed with ice cream, another with red bean paste – is best forgotten.

Surely Satsuki will be more cheerful when the adjoining kaiseki restaurant is full and fans claim all the seats at the sushi counter. Toshio is a star. But while he is special, the sushi is mostly not. Not compared to the master works at O Ya. Or the less expensive adventure of Shuko. Or the mastery of early Masa. Nor Nakazawa before the chef got Americanized and too chatty. What we ate was certainly well done, and I appreciate the demandingly curated swimmers. But I want more thrills to justify the $250 price. Our bill with the $35 sake, including tax and service already added, was $345 each.

Even so, now that the sludge is melted, I plan to go back for kaiseki.

114 West 47th Street between Sixth Avenue and Broadway. 212 278 0047. Open for reservations at 5:30pm Sunset menu $130, 7:30pm, and 9:30pm, full omakase $250. Three Pillars Bar & Lounge open Monday through Saturday 5 pm to 11:3 pm. Reservations accepted now for Kaiseki dining, starting April 6.

In her role as restaurant critic of New York Magazine (1968 to January 2002) Detroit-born Gael Greene helped change the way New Yorkers (and many Americans) think about food. A scholarly anthropologist could trace the evolution of New York restaurants on a timeline that would reflect her passions and taste over 30 years from Le Pavillon to nouvelle cuisine to couturier pizzas, pastas and hot fudge sundaes, to more healthful eating. But not to foams and herb sorbet; she loathes them.

As co-founder with James Beard and a continuing force behind Citymeals-on-Wheels as board chair, Ms. Greene has made a significant impact on the city of New York. For her work with Citymeals, Greene has received numerous awards and was honored as the Humanitarian of the Year (l992) by the James Beard Foundation. She is the winner of the International Association of Cooking Professionals magazine writing award, 2000, and a Silver Spoon from Food Arts magazine.

Ms. Greene's memoir, "Insatiable, Tales from a Life of Delicious Excess"(www.insatiable-critic.com/Insatiable_Book.aspx )was published April 2006. Earlier non-fiction books include "Delicious Sex, A Gourmet Guide for Women and the Men Who Want to Love Them Better" and "BITE: A New York Restaurant Strategy." Her two novels, "Blue skies, No Candy" and "Doctor Love" were New York Times best sellers.

Visit her website at: www.insatiable-critic.com